Just a quick test post to see if embeds work, etc.

Test page

China’s brightest children are being recruited to develop AI ‘killer bots’

This can't be good.

The Prisoner at 50

To coincide with The Prisoner turning 50, here's my essay on the show and its remarkable prescience.

The essay originally ran in the back of Headspace #2, available here.

Page layout and design is by the awesome Christopher Kosek

Cheers to Ryan for being a sport about me putting this up.

Enjoy!

A Shameful Narrative

This piece originally ran in my newsletter. Inspired by this fantastic and (unfortunately) much needed article by Nick Hanover I am reposting it here too.

Intro

So, as well as my 'make comics' hat I am currently (albeit slowly) working my way through a diploma in journalism from the NCTJ. This is because I believe in overloading myself with work.

A lot of the initial assignments started off pretty low level, but as the course has gone on the assignments have gotten much more involved, taking up more time and requiring me to actually gather research, interview subjects and the like myself. It's almost like they're training me to be a journalist.

An assignment last year required me to write up a feature, conducting interviews as part of it. So, I set about crafting a feature about gender inequality in the comics industry. My plan was to interview women from the industry at three levels – retail, criticism and creative (be that an artist, writer, colorist, editor, etc.).

I had a very specific shortlist of people I wanted to interview when I was brainstorming the feature. Alas, after initial promising replies the majority of people I reached out to didn't end up being involved. In all cases, this was due to scheduling, current workload and the cold hard reality of a deadline.

So, the article had to be completely restructured in a short amount of time and I only managed to interview a single person. That said, I think Rebecca Epstein did an absolutely fantastic job at voicing the frustration and exasperation many feel about the state of the industry. She can be found on Twitter, here. Seek her work out wherever you can find it.

The basic premise of the article was to use data I'd culled from October 2016's solicitations as a jumping off point to talk about the rampant inequality still present in mainstream comics. These findings (in handy list form) were:

DC

- DC has a potential of 154 creative slots (taking into consideration writers and artists only as they don't give details of letterers, colourists, etc on the solicitation source I was using).

- Out of those 154, there was a total of 23 female creators which is 14.94% of the total available slots.

- There were 77 DC titles in total for October 2016

- Female creators were represented in 17 of those 77 titles which are 22.8% of the total.

- If we do NOT include double shipping titles that total falls to 15 which is 20%.

- Out of those 15 titles, 7 were female-centric books (featuring a female lead or a team where female characters are prominent on the cover and other promotional material)

- There are 11 writer slots and 12 artist slots (one book had two female artists) taken by women, a fairly even split.

- Of those 11 writer slots, 7 are female-centric books, 2 are ensemble books and 2 are male-centric.

- Of those 12 artist slots, 6 are female-centric books, 3 are ensemble books and 3 are male-centric.

Marvel

- Marvel has a potential of 168 creative slots based on the same configuration as above.

- Out of those 168, there was a total of 24 female creators which is 14.29% of the total available slots.

- There were 84 Marvel titles in total for October.

- Female creators were represented in 19 of those titles which are 22.62% of the total.

- Out of those 19 titles, 12 were female-centric books.

- There are 11 writer slots and 13 artist slots (two of the books have 2 female artists each) taken by women.

- Of those 11 writer slots, 6 are on female lead books, 1 on an ensemble book and 4 on male lead books.

- Of the 13 artist slots, 11 were on female lead books with the 2 remaining artists both on the same ensemble/anthology book.

///

The piece that resulted from the above data is featured below:

Part of the Problem: Marvel, DC and the comic industry's gender problem

Despite repeated calls for equal representation in the comics industry, new figures show Marvel and D.C Comics, the established ‘Big Two’ of mainstream comics, are still failing in their efforts to provide a creative platform for female creators.

These figures, gleaned from a list of October 2016 releases, show only 22% of the titles listed have a female creator involved. This under-representation has continued to plague the industry, despite Marvel reporting women now make up 40% of its readership, a figure that looks set to rise year on year. Both companies are now guilty of failing to accurately reflect their readership in their choice of creative teams. When presented with the findings, comics creator, critic and commentator, Rebecca Epstein, asks if this is just indicative of a larger problem:

“In an industry plagued by dishonest and misogynistic incidents against women, are the findings merely the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the comics industry's attitudes towards female creators?”

Her question raises uncomfortable truths, but ones worth investigating.

A Shameful Narrative

For decades, comics was seen as a male dominated industry, in terms of both its consumers and creators. Comic book shops almost seemed to be designed to exclude, places marked as boys only. However, in recent years, the rise of the internet and the burgeoning popularity of comics culture has given rise to entire networks and online spaces where anyone can discuss characters, story lines, and creators without the fear of jokes, abuse or belittlement.

Slowly but surely, there a surge in comics being produced that encourage inclusivity and catered for all tastes. But this influx of new blood was met with resistance by some as parts of the industry struggled to move past its myopic, boys club past. It wasn’t long before horror stories emerged concerning the treatment of female creators and fans. The networks and online spaces that had fostered this surge towards inclusivity were now under attack.

One of the most recent, and well known, examples concerned DC editor, Eddie Berganza. Despite a well-chronicled history of sexual harassment of female employees, he was kept on as editor by the company. In fact, DC also instituted an informal policy that female employees be barred from working in the same office as Berganza, thereby tacitly acknowledging the problem whilst also ignoring it [^Footnote1].

This example is just one among many when it comes to instances of predatory and disgusting behaviour towards female creators and staff.

Such a shameful narrative threaded through the industry immediately precludes and diverts existing and potential creators from wanting to pursue work with these companies. Epstein argues that responsibility should be the first port of call for those at the top.

“First, every comics publisher needs to start being held accountable to state and federal laws that prevent toxic work environments, sexual harassment, and sexism in the workplace. Figures like Scott Allie and Eddie Berganza should be fired immediately. In fact, all current leadership in Marvel and DC should be overhauled due to their past protection of sexual predators and replaced with people who openly hold themselves responsible for what their companies and the industry should look like. Only after this, can we truly talk about [the] fair hiring of creatives.”

Alternative Independence

It's these problems, as well as cronyism and the boys club mentality that Epstein argues, has prevented and undermined efforts by female creators to break into mainstream comics.

“At least one woman has admitted to turning down a Superman book due to fears of working with Berganza. Even then, the people involved in the hiring processes in these companies are grossly incompetent and lazy. They don't seek out fresh new talent, they tend to hire their friends over and over again. And because most of these people have worked in the company for at least 20 years, their friends are the same older, white demographic that wanted to break into comics 20 years ago.”

As a result of this, upcoming and established female creators find a more welcoming destination amid independent comic companies or self publishing. As well as providing a more balanced outlook, publishing work by female creators across multiple genres, such approaches also provide more in the way of creative control and financial reward.

Epstein even recommends this as a primary avenue for female creatives looking to break into the industry. Superheroes are no longer the only draw for comic book readers after all.

An Endless Loop

It's only when looking at the stories and experiences of female creators that it becomes obvious the figures discovered are merely a smattering of the problems in the comic book industry when it comes to gender equality and diversity. For women working in the industry, these findings don't come as a shock, as Epstein explains:

“No, I've watched these same figures for years—possibly even before becoming a comics critic and journalist. These are the best they have ever been. What's truly shocking is the type of behaviour from comic professionals behind the scenes that ensure that figures stay at such a low rate. It's really no wonder after hearing so many horror stories from women who tried to break into the industry (as well as nearly experiencing one of my own).”

Unfortunately, at the time of writing, nothing much has changed in the industry and new revelations follow a seemingly predicated cycle. New information will come to light that a male creator, editor or executive have abused their position and harassed or intimidated a female employee, creator or fan.

The comics industry will convulse in outrage and anger, vehemently attacking and condemning the guilty party. Think pieces and commentary will appear stating this is a problem the industry needs to fix. The accused and guilty will batten down the hatches, either denying their behaviour outright, carrying on as if nothing has happened or issuing a stock apology before business as usual resumes. Then the news cycle of the industry finds something else to latch on to and the memory of all that has gone on fades, staying only with the victim and a select circle of journalists, critics and insiders.

The Buck Stops Here

There is, of course, a responsibility of male creators in the industry that all should be observing. Don't be a dick. Don't be a creep. Don’t condone predatory or sexist behaviour. Speak up and speak out. These should be unspoken rules, but the fact I'm having to type them speaks volumes.

But the above is merely an extension, a causation of the policies the big two continue to pursue. The vast majority of those who have been accused of harassment, assault or intimidation are still working in the industry. The companies they work for, the same companies who champion their female characters and growing female readership, does not give its male creators and employees boundaries, rules or a set of consequences.

By refusing to dole out punishment and justice to those undermining the efforts to diversify and grow the industry they ensure it will be forever trapped in amber and that the misogynistic attitudes so prevalent will continue.

[^Footnote1]: The latter part of this sentence sums up the problems rife in the industry in a nutshell.

Aspects and Alters – Psychology, the Hero’s Journey and the descent into hell in Moon Knight – Part Three

This phase of Marc’s journey seems to align with Campbell’s idea of the ‘road of trials’:

“Once having traversed the threshold, the hero moves in a dream landscape of curiously fluid, ambiguous forms, where he must survive a succession of trials. This is a favorite phase of the myth-adventure. It has produced a world literature of miraculous tests and ordeals. The hero is covertly aided by the advice, amulets, and secret agents of the supernatural helper whom he met before his entrance into this region. Or it may be that he here discovers for the first time that there is a benign power everywhere supporting him in his superhuman passage. The original departure into the land of trials represented only the beginning of the long and really perilous path of initiatory conquests and moments of illumination. Dragons have now to be slain and surprising barriers passed — again, again, and again. Meanwhile there will be a multitude of preliminary victories, unretainable ecstasies and momentary glimpses of the wonderful land.”

These tests and trials will often come in threes, an interesting number when you consider Marc’s warring identities and how they begin to overlap before they finally coalesce at the end of Issue #8 with all three arriving back at the foot of the pyramid to be brought face to face with Marc. Action-wise so much has happened, but still we circle back to where one section of the story ended but now serves as the beginning of the next.

It’s here Marc subsumes the various aspects of his personality through violence, language and acceptance. Once this is done he realises his final goal – to kill Khonshu.

///

The next arc opens with Marc’s childhood and his first ‘meeting’ with the Steven Grant identity. We see Marc scrawling a spaceman fighting wolves on the pavement in chalk. Not only is this a reference back to the previous arc, but it also shows Marc was prone to flights of fancy from a very early age. These two strands of narrative follow the ‘present’ in the othervoid and Marc’s past from his childhood to his first meeting with Khonshu.

It’s back in ‘the present’ that Marc begins another descent into the sewers before descending once again into the othervoid. Smallwood shows this with a double page splash coated in inky black tracing Marc’s descent, and orienting the panels to the reader is forced to turn the page to track it. The reader’s physical orientation shifts with Marc’s perception. Smallwood then chooses to turn Marc’s final descent upside down, making it look like an ascent. Again, we have to shift our orientation to understand, just like Marc. But it also references back to Marc’s first ascent on those stairs as the panel sizes reduced. An descent masquerading as an ascent. Here that is switched, showing Marc, finally, is on the right path.

The next set of flashbacks concerns Marc’s time spent in the mental hospital he found himself in during Issue #1. Here it looks considerably better, not faded and drab as we saw previously. Even Dr Emmet and Doug are here, now dressed in soft, pastel pink rather than the imposing red or white. As Marc returns home for his father’s funeral he’s once again drawn to the moon and the voice of Khonshu as he was in one of the earlier childhood sequences.

This suggests that Khonshu may in fact be just another aspect of Marc that has been manifesting for some time and that when he puts on the Moon Knight mask he is acknowledging that voice.

As we move back to ‘the present’ Marc is fighting Set and his minions. The fight sequence here, another double page splash, is framed in acres of white space with non-existent panel borders. This has the effect of drawing the eye and focusing it, giving us clarity as Marc achieves his own.

As we flip back into flashbacks we are looking up at the moon once more as Marc stands confused out in the Iraqi desert. It’s here he is discharged from the military and soon after we find him lost to violence in an underground fighting ring.

These flashback sequences show us Marc trying to ignore the voice of Khonshu, running halfway across the world to escape it. The constant circles and numerous refusals to the call mirror the choices he’s made throughout this story. He is constantly trying to hide or ignore the voices within. It’s only when he accepts them, moves towards them that some kind of solution and peace occurs.

As Issue #12 begins Marc finds himself bound to a sacrificial altar, looking almost exactly like he did in an earlier hospital sequence.

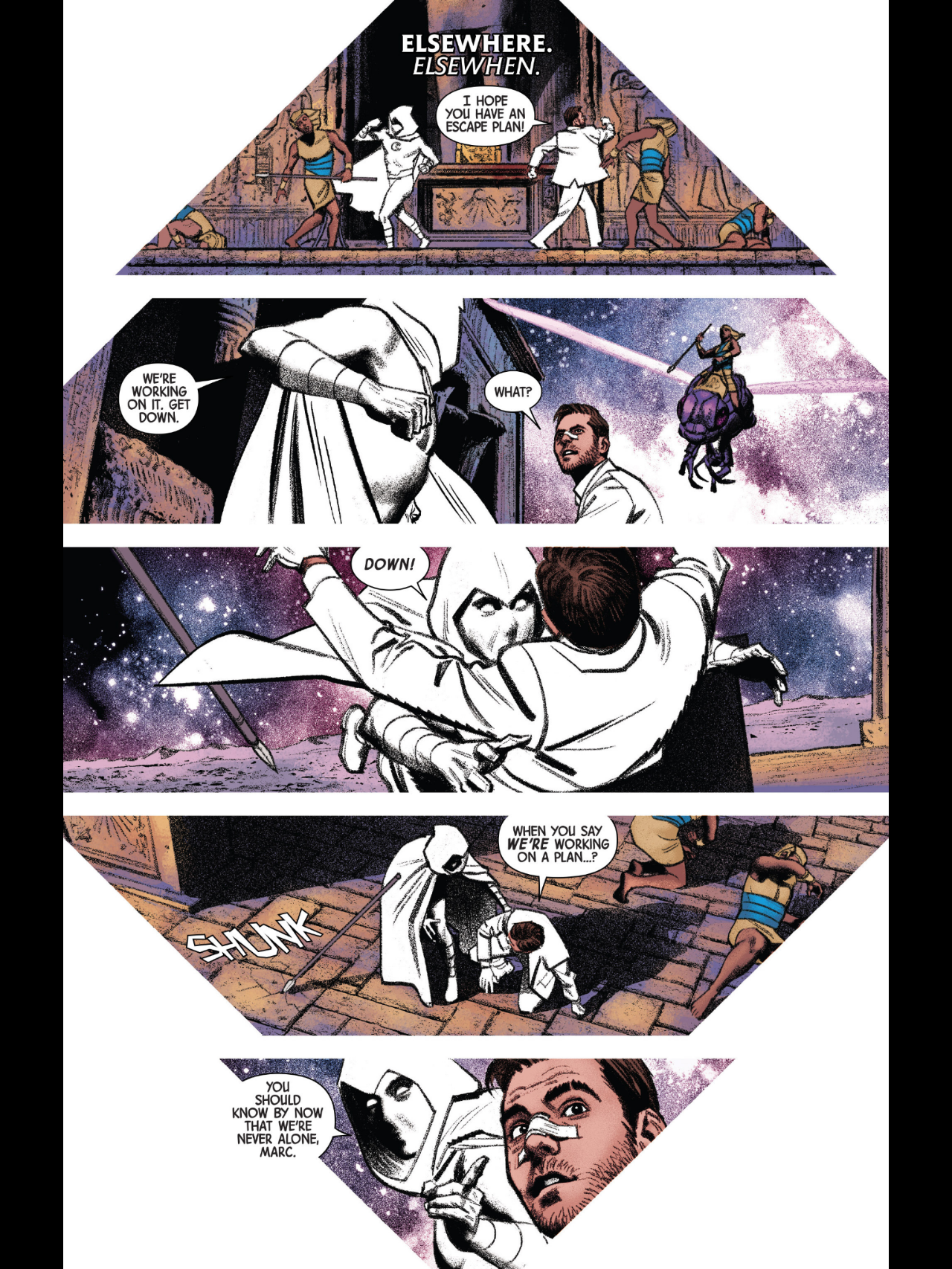

The central panel is buttressed by two triangular panels, producing movements in ascent and descent, as well as showing us two mirrored pyramids, suggesting some equilibrium. Marc is nearing some kind of breakthrough.

Later this structure is elaborated on with a set of extra panels either side of the central one inserted. The shape of the middle three panels also take on a triangular aspect that completes the idea of a mirrored pyramid. That these panels show us Marc and Moon Knight alongside each other at last doubles down on the idea of Marc approaching enlightenment. Soon after, the two other vanquished identities return to lend a helping hand too.

This supports the ego-death theory, with Marc going through the stages of separation, then transition before arriving here – incorporation. Here in the othervoid he is also in the state ripe for ego-death – “beyond words, beyond space-time, beyond self.”

As we move into Issue #13 we begin to understand this last set of trials is all about the atonement with the father/Khonshu. Campbell defined one aspect of this stage as:

“The problem of the hero going to meet the father is to open his soul beyond terror to such a degree that he will be ripe to understand how the sickening and insane tragedies of this vast and ruthless cosmos are completely validated in the majesty of Being. The hero transcends life with its peculiar blind spot and for a moment rises to a glimpse of the source. He beholds the face of the father, understands—and the two are atoned.”

Marc, alone, ventures into the pyramid once more as Khonshu’s voice rings out, welcoming Marc’s return. On the next page it’s revealed that the othervoid, the ‘present’, the entire story has been occurring in Marc’s mind the entire time. Like his identities they now start to coalesce and become one. Incorporation.

As Marc descends into the final ‘innermost cave’, the dark recesses of his own mind, he states his intention of being here to ‘kill’ Khonshu. As he punches through more of the deities tricks he arrives back in the subway – another return to the beginning.

Highlighting this is the sequence being juxtaposed with a flashback to Marc’s origin a Moon Knight as he is beaten and left for dead by another father figure, Bushman, as Frenchie looks on helplessly. These two moments, like so many others across the story, are reflections of each other, intertwined tightly.

As Marc comes to and moves through the desert he’s met by Steven and Jake who tell him to rest. When he wakes again it is night, the moon full and bright in the sky. Khonshu’s voice rings out. Marc, finally, begins to crawl towards it arriving at Khonshu’s temple as he did on the very first page of the story.

Here Marc supplicates himself before Khonshu for the first time. At death’s door, Marc essentially gives himself over to Khonshu, letting the voice and violence into his mind. This is the price of coming back from the dead but also a reflection of what he must do in the othervoid, casting the violence and Khonshu’s voice out of his mind.

As the two timelines merge Marc is surrounded by various external threats – Marlene, Werewolves, Bushman and villains past. Instead of giving in to the voice and anger this time he clears his mind and speaks directly to Khonshu.

Marc states he knows Khonshu is his madness and nothing more. Flying fists, crescent darts and roundhouse kicks are set aside for the biggest boon of all – acceptance. Once Marc accepts his madness, instead of fighting against it like he always has, he is able to shatter and rid himself of Khonshu’s influence.

Marc is now a master of two worlds. Balance is achieved. He opens his eyes to find himself on a familiar looking rooftop looking up at a familiar looking moon. We’re back where we started, but we’ve come so far.

Aspects and Alters – Psychology, the Hero’s Journey and the descent into hell in Moon Knight – Part Two

In the second issue Spector finally meets Frenchie in the hospital, his longtime friend and co-pilot. He is the last ally of Marc to be revealed and this marks the beginning of what Campbell calls the Initiation sequence, whereby the protagonist will face a number of tasks and trials with the assistance of others.

As before, this passage into a new phase of the journey is preceded by Marc being strapped to the shock therapy table once again, the panels moving downward in exclamation once more. He awakens, in full costume, kneeling before Khonshu. Initially, Marc is unable to communicate with Khonshu and this small detail plays again into the idea of a circular, reflective narrative. Later, when we see Marc’s first run in with Khonshu in the desert Marc misunderstands the deity. This recurrence, along with their physical positioning within the panel, suggests Marc and Khonshu have never been completely aligned.

The circular motif present in the visuals of the story is also reflective of the structure of Campbell’s Hero’s Journey. This is almost always displayed on a circular diagram, something that implied repetition and a protagonist constantly having to learn new things, acquire new boons and go on new quests. This is something we see with Marc himself as he goes through a kind of ‘mini-journey’ each issue, getting closer to the final truth with each attempt.

These attempts fit with a macro-structure facsimile of Campbell’s ideas that occurs across the entire run.

It’s revealed during this issue the dream-space Marc is sharing with Khonshu is somewhere called ‘the othervoid’, a place beyond time and space. According to Timothy Leary’s ideas about ego-death, there couldn’t be a better place for Marc to reach some kind of inner peace. He stated that ego-death was an idea of transcendence “beyond words, beyond space-time, beyond self”.

As Marc and his allies escape, they head down this time instead of up. They descend the stairs and arrive in the cold, grey subways – a mirror of the beginning of the previous issue where Marc arrived here alone.

///

The next part of the story involves Marc gradually losing these allies (Frenchie falls in battle, Crawley sacrifices his soul, etc.) This tallies with thoughts Leary had about LSD and its role in ego-death. He argued the drug stripped away the ego’s defenses and it could be argued this is what’s happening here as Marc loses all of his allies bar one. He doesn’t know it yet, but this battle is one that’s only going to be won by him alone.

This is reinforced with Marc’s conversation with Khonshu in the toilet (tiled half in red) as he tells Marc he will need to ‘lose a lot more’ in the way of friends and allies before this over.

This is immediately juxtaposed with the awakening of Marlene before she and Marc head out with her to the giant pyramid that towers above the New York skyline.

This double page splash shows Marc and Marlene looking up to the pyramid’s peak and preparing for an ascent, again as the panels descend in size. This contradiction, like the other sequences earlier, plays into the warring and contradictory nature of Marc’s mind. All is not at peace yet, there is still dissonance here.

As they ascend they are met with perhaps our first true ‘Threshold Guardian’, the old version of Moon Knight standing guard and ready to fight. These guardians were another aspect of Campbell’s monomyth, standing at the edge of a new way of understanding for the protagonist and had to be beaten before new knowledge was gained.

The pair tussle almost immediately with Marc taking a moon-shaped crescent dart and stabbing this Moon Knight in the gut. The placement of this attack is the same as the wound Marc clutches in the opening scene of Issue #1, hinting that Marc is actively hurting himself with his current actions.

It also acts as a precursor for what comes next, a stretch of story where Marc’s personality and mind is shattered into his various identities and he enters into conflict with them, attempting to reconcile them all, with each one of them acting as a threshold guardian into themselves.

In DID theory the various identities are often called alters or ego states. Some argue these two terms signify very different things. They argue ego states are an ‘organized system of behavior and experience whose elements are bound together by some common principle’ whereas alters ‘have their own identities, involving a center of initiative and experience, they have a characteristic self representation, which may be different from how the patient is generally seen or perceived’. On those definitions it’s clear that Steven Grant, Jake Lockley, etc. are alters rather than ego states.

As Marc steps through the door inside the pyramid we are introduced to a new alter – a literal Moon Knight, protecting the Earth and lunar landscape from a horde of werewolves, all beautifully rendered by James Stokoe’s scratchy, kinetic artwork. He also brings in the colour red to highlight danger as the hordes chase the Moon Knight towards another door.

Those with DID are said to switch identities when threatened psycho-socially. Here, the threat is imagined, but no less real to Marc and he heads through the door and into another alter – the Hollywood bigwig, Steven Grant. The art switches up again, morphing into a classic style by Wilfredo Torres with lush, rich colours by Michael Garland.

Here Grant/Spector are met by Marlene, completely cloaked in red, acting as a herald to warn Marc about his pursuers as he runs through another (red) door into a third identity – Jake Lockley.

Lockley’s world is drenched in sleaze, beautifully brought to life by Francesco Francavilla’s art and noir-ish colours that give the world a neon glow. But, it’s only a brief stop, as Marc’s pursuers continue their chase, prompting Marc to come full circle and escape through another door that leads him back to where he started once again – the pyramid.

Here he comes face to face with the Moon Knight he stabbed in the gut before entering the pyramid. He unmasks to reveal...Khonshu! The mirroring of the wound as discussed earlier suggests Khonshu is very much a part of Marc and vice versa. They are inextricably linked.

Marc, having none of this, begins another descent, this time throwing himself off the side of the pyramid. The panels decrease in size, as before, but this time the page ends not with a close up on Marc or black, but a shot of happier times as Marc jokes with all of the allies he has now lost. This is colored in the same diffuse style as the other ‘flashes’ of the past and due to its placement it suggests it is a place Marc desperately wants to return to.

As he lies battered and bloodied at the foot of the pyramid he suddenly awakes to find himself in the shoes of Steven Grant, wholly accepting of this reality and his placement in it. Marc is hiding, deluding himself once again. More tests are on their way.

Aspects and Alters – Psychology, the Hero’s Journey and the descent into hell in Moon Knight – Part One

During the Ellis/Shalvey/Bellaire run on Moon Knight there’s a sequence where the titular hero battles through a mushroom-induced dreamscape, fantastically rendered in rainbow-like colours before he crashes through what looks like a brain and faces the force behind it all.

The more recent run by Jeff Lemire, Greg Smallwood and Jordie Bellaire takes this idea of Moon Knight fighting on a metaphorical landscape and extrapolates it into an internal struggle within the mind of Marc Spector himself. By doing so, as well as using recurring visual motifs, they produce a shattered, fragmented version of Joseph Campbell’s ‘Hero’s Journey’.

Mix this in with overt references to Marc’s disorder and an undercurrent of good old Jungian Ego-Death and you have a story that is no less dramatically loaded than one taking place in the physical plane.

///

We start, of course, with the moon. Straight away we notice Smallwood’s line work is looser, coarser even, with Bellaire’s diffuse colours giving the opening page the feel of a dream. Marc hears a voice, rendered in a hieroglyph style font by Corey Petit. The letters are balloon-less. Khonshu is everywhere.

Directly beneath the moon is our first full look at Marc, glancing upwards in reverence. Further down is a shot of Marc dwarfed by a temple and statue of Khonshu. Again, Marc is at the feet of the deity. We’re on Page One and we already have two examples of Marc beneath, or in supplication to, the moon and/or Khonshu. This will recur again and again as the story continues.

The moon, Marc, the temple and Khonshu are all aligned down the central axis of the page. Everything is in balance, in order, as it should be. Khonshu’s voice beckons Marc onwards, marking what Campbell refers to as ‘The Departure’ with the protagonist receiving the call to adventure (usually from a mentor-like figure).

In Christopher Vogler’s ‘The Writer’s Journey’ (a kind of marriage between a ‘how to’ book and a primer on Campbellian structure) he names ‘The Shapeshifter’ as one of seven archetypes that occur in fiction. The rub is that ‘The Shapeshifter’ can change roles throughout the narrative, becoming a different archetype as the protagonist moves through the narrative. Khonshu has the hallmarks of the mentor figure here, but it won’t always be that way. As Marc uncovers the truth the sands will shift.

On the second page Marc enters what looks like a graffiti-laden subway. He's descended into the temple into the bowels of a city to be met with a doorway of glowing yellow light. The idea and physical act of descent is a recurring visual motif, directly linking to Campbell’s idea of the descent into the underworld. Again, Marc is aligned with the door, his goal, and Khonshu’s voice, down the centre of the page. One other thing worth keeping in mind is that Marc is injured, clutching a stomach wound and complaining that he “feels like his guts are slipping out”. Marc continues towards the light.

Next, Marc comes face to face with Khonshu, standing before the seated deity before conceding his stance and lowering himself to be at the God’s feet. It’s here we learn Marc and Khonshu have the same goal, rebirth, but their methods and proposed end games are entirely different. As Marc pulls the Moon Knight mask over his face he is subject to a flood of memories of his disparate identities as Smallwood’s diffuse style gives way to something more solid and traditional.

As Marc attunes to this new reality, Bellaire dots the pages with tiny splashes of yellow and red. Yellow often has positive aspects (warmth and happiness), but can also signify deceit, our first hint all is not as it seems.

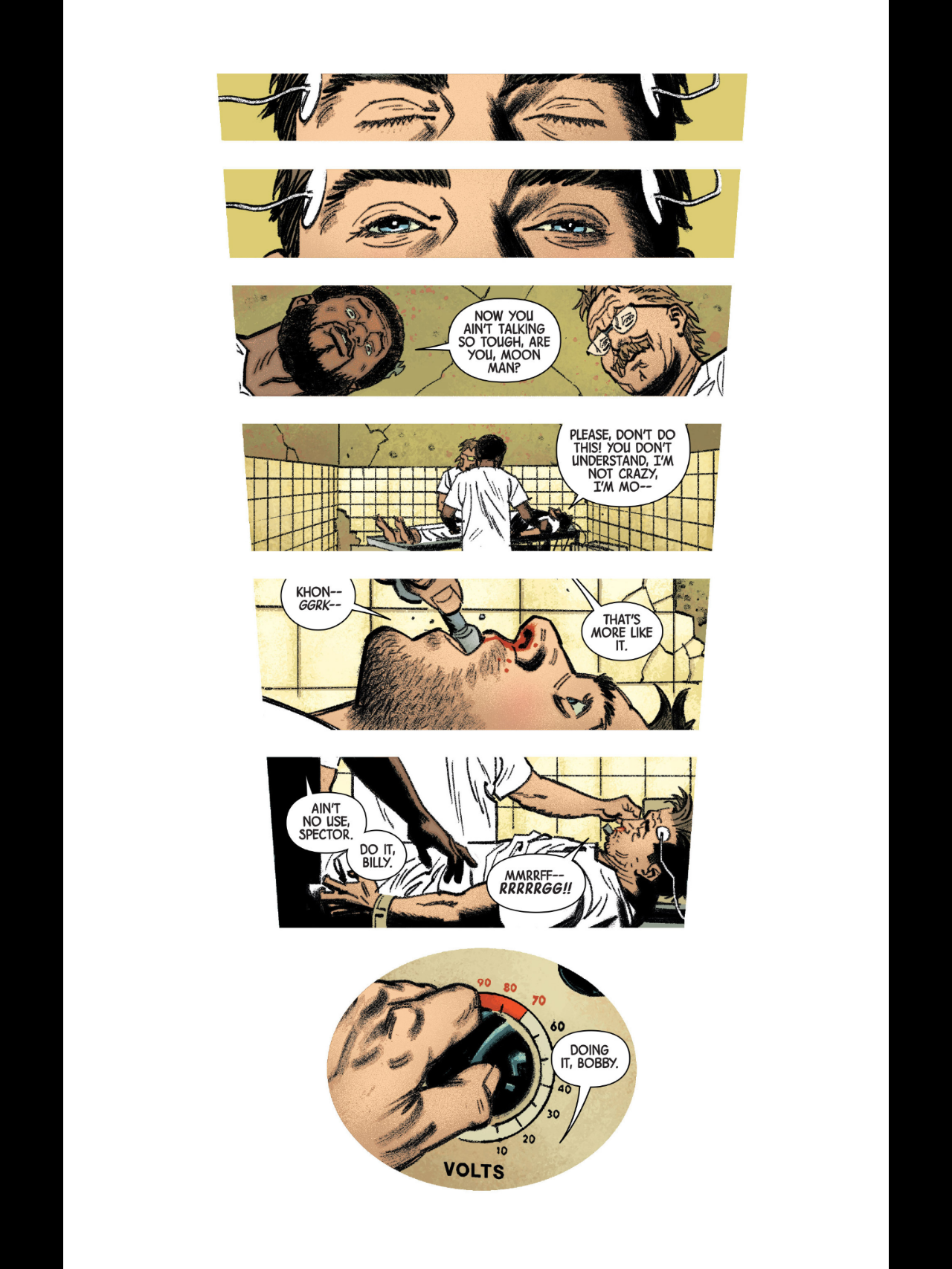

Red though? Red is not good either. The orderlies, Marc being punched and kicked, his bloodied nose and even the syringe he receives are all accentuated by red. By rooting the page in a simpler pallette than what’s come before, Bellaire gives the reader the impression of a more tangible reality than the one we opened with. It’s a clever way to fool the reader into thinking this is reality and Marc has finally cracked.

As the syringe delivers its payload we get a series of wide panels that diminish in size as we move our eyes downward, watching as Marc descends into the white void. As he regains consciousness the structure holds with the panels decreasing in size to a circular panel with the voltage switch on the shock therapy machine serving as a visual dot on this exclamation mark style visual. The room, tiled in yellow, is offset by the tiny splashes of red on Marc’s bloodied nose and the dial on the machine.

As the current surges through Marc’s body we see a shot of him arching his back in pain, as if awaking from a slumber or nightmare. This pose and visual will also be repeated throughout the story, often marking a departure point or passage into another reality for Marc. Pain is what’s guiding him.

When Marc awakens he is sat, posed almost like Khonshu surveying his domain – a severely decrepit looking mental hospital. Smallwood gives the room an art deco look that has gone to seed, hinting at past glories now wilted, a nice visual tie to Marc’s current status. It’s here we also meet Marc’s allies – Gena, Crawley and Marlene (but no Frenchie yet). As he sees them for the first time each are accompanied by a panel harkening back to days gone by using the hazy dreamlike style of the opening pages.

Dr Emmet, in charge of Marc’s treatment, is introduced soon after (dressed in red of course). She tells Marc the Moon Knight mythos is all a lie, a narrative sat atop the one true reality, blinding Marc from seeing things as they really are. She stands at one point and Marc, with his head bowed, seems smaller than those who seek to control him.

As night falls, Marc lies still in his bed, the stark whites and blacks making him look a sarcophagus. When he attempts to break out his cell we see a shot of the orderlies entering and then Marc standing before them in a makeshift Moon Knight costume. In the central panel he is framed by the orderlies arms, framing him, but giving a downward triangular shape, a pyramid that also serves to lead the eyes downward to a reveal of the orderlies as mythical creatures. Marc is literally standing between two planes of reality.

As Marc launches himself at the orderlies the yellow, so prominent up until now, is overwhelmed by whole panels bathed in red. They all show Marc lashing out violently. It hints that violence, Marc’s default mode of thinking, may not be the answer.

Marc then attempts to escape the hospital by ascending a staircase leading to the roof. As he does, the panels decrease in size again, creating a sense of descent. However this time , due to mark moving upwards, the panel size creates a sense of dissonance. This path is not the right one.

As Marc looks out over the rooftops he’s met with the sight of a New York buried beneath sand, as a gigantic pyramid dominates the skyline. As Marc grapples with what he’s seeing the page is laid out into fifteen panels, dividing Marc and giving us a metaphor for his fracturing psyche. The page also places Marc directly beneath the moon once more as Khonshu’s voice rings out.

The location may have changed, but we are right back where we started. This is Marc crossing the 'First Threshold' as Campbell coined it, but failing to progress any further. There is still too much internal conflict.

It becomes apparent that to win this battle, maybe his most important battle, Marc is going to have to adhere to another Jungian idea – the death of the ego.

Now

Reading

I am currently reading:

- Rosewater by Tade Thompson

- Gnomon by Nick Harkaway

- Carbon Ideologies Book 1 by William T. Vollman

Tools

- I listen to podcasts via Overcast.

- I trawl RSS, newsletters and Twitter using Feedbin.

- I send out my newsletter via ButtonDown.

Disorder (2015)

Disorder begins with a flutter.

A smattering of birdsong and a gentle breeze fade into our ears as the screen remains black. It is the calm before the storm, the only real peace and tranquility we, and it’s protagonist, will know until the credits roll.

Disorder is the tale of Vincent (Matthias Schoenaerts), a soldier who finds himself without a purpose when he is cast aside due to his burgeoning anxiety and PTSD. Before long he finds work with a group of fellow ex-soldiers providing security for a party at a beautiful house on the French Riviera.

During the party Vincent discovers the host, Whalid, may be involved in the murky world of political slush funds and arms dealing. Soon after, he is tasked with protecting Whalid's wife, Jessie (Diane Kruger) and son, Ali whilst he is away on business.

The film opens with Vincent jogging with other soldiers. He becomes unfocused in the frame as he bounds towards us, the camera locked tight on his face. The sounds of nature soon fall away and we're left with a pulsing electronic beat as we slowly realise that Vincent's nose is bleeding.

This opening thirty seconds is a portent of how Winocour chooses to show Vincent's condition throughout the film. She brings us in close on Vincent, often at an unusual angle, whilst discordant sounds and the pounding bassline of Gesaffelstein's soundtrack block everything else out. Everything in Vincent's world is amplified. Car engines become an almighty roar and a simple garden sprinkler is a rogue wave tearing everything asunder.

When Vincent is cast out of the army he returns to small flat in a faceless tower block. He shouts for his mother but gets no reply. His bedroom seems frozen in time, like that of a teenager, all football pennants and tattered posters. Vincent is a ghost, moving through our world whilst being entirely separate from it.

As he strides through the party this idea is taken further, taking on an aspect of class. Vincent is a product of a war waged for profit and power, a war conducted by some of the very people he is now protecting, people who don't even see him unless it's to ask for more ice.

Schoenaerts plays Vincent as a bundle of tightly wound and frayed nerves. He shoots cynical, resentful smirks and knowing smiles at those around him. Several times during the party scene he follows guests and eavesdrops. He has a good nose for trouble and an eye for detail but it's only because he's seeking it out, eager to let go of something festering inside of him.

With this in mind it's easy to see why Vincent accepts the job of watching over Jessie whilst Whalid is away. He regains some semblance of structure and purpose, but there's also the possibility he may be called on to unleash the demons inside.

As Vincent's time on protection detail rolls on the tension winds tighter and tighter. As he watches over Jessie and Ali at the beach, Winocour switches pace, shifting down into slow motion as the soundtrack pounds, rings and roars. We see what Vincent sees, slow lingering shots of two women laughing and smiling, a runner sprinting past Jessie, men standing nearby on mobile phones – everything is suspicious, everything is a threat. This is Vincent's world.

As the film enters its final act Winocour spends a little time tightening the bond between Jessie and Vincent. When Vincent first sees Jessie he does so from behind a barred window. Later he watches her on a monitor as he looks at the house's CCTV. Barriers, physical or otherwise, exist between the two characters for a large part of the movie. At several points during the movie we see Vincent's stare linger on Jessie. There's an obvious attraction to her on his part, but there also seems to be a fascination. She lives in a world and class so far removed from his own that she seems otherworldly to him. In turn, Jessie is cold towards Vincent initially, even fearful of him.

Later on, Vincent calls in a friend, Denis, for some help in watching over the house. After Vincent does his rounds he comes across Denis flirting with Jessie. It comes easily to Denis and Vincent can only watch from the other side of the table, smiling uncomfortably as he remains trapped beneath his anguish.

But, in a scene towards the end of the movie, Jessie and Vincent watch television. Jessie, in an off the cuff piece of dialogue, says she could see Vincent living in Canada hunting for bears and the pair begin to laugh about it. It's a small, sweet moment built towards by Schoenarts' and Venora's subtle and understated performances. It's the first time we see Vincent laugh, but it's also the first time another character sees Vincent as something more than his surface suggests.

It's at this precise moment that Winocour chooses to plunge the world into literal and metaphorical darkness as the threat of violence that has been hanging over the entire film finally makes its presence known. The house, previously shown as light and airy, now becomes a labyrinth of shadow and chaos thanks to DP Georges Lechaptois.

Vincent, of course, knew this was coming and acts accordingly. There is no efficiently choreographed set-pieces here, no balletic gunfights. Violence is ugly, sudden and messy. Limbs flail, glass shatters and men do not get up when they're bleeding out from the gut.

It's easy to miss it during the ferocity of the finale, but the score drops out almost completely during this final sequence. The chaos inside of Vincent is finally externalized and catharsis is a blood smeared coffee table.

It's only now, when the violence he has been seeking all along is over, that some kind of calm washes over Vincent for the first time. Despite this, the film ends on an uncertain note. Peace (and quiet) reigns, but it's unclear whether Vincent has finally crossed the divide or whether he still remains on the other side looking in.